The “Alexagate” is an over-the-top answer to real privacy concerns.

By Jared Newman 2020-07-27

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/90532150/you-can-now-buy-an-amazon-echo-add-on-that-stops-alexa-from-listening

Right now, my Amazon Echo speaker is looking a lot uglier than usual.

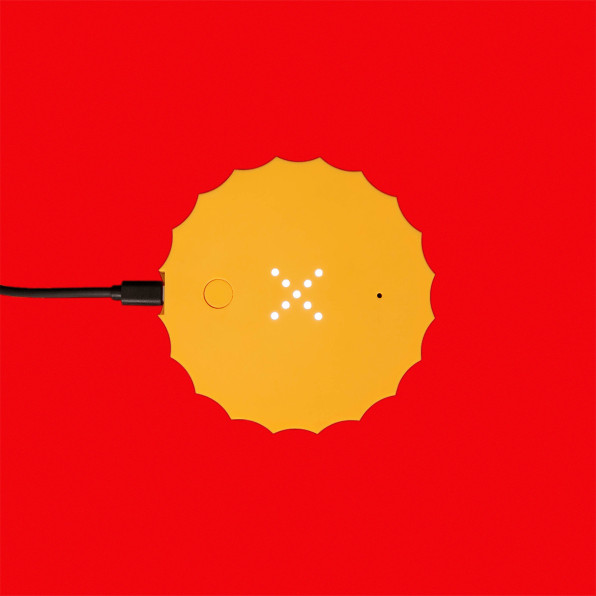

Protruding from the top of the speaker is a three-inch-tall cylinder of yellow plastic, with a sunburst pattern around the edges. When it’s plugged in and turned on, an array of ultrasonic speakers on the device’s underside confuse the Echo’s always-on microphones, rendering Alexa inoperable until I either clap three times or triple-tap the top of the cylinder.

The device, called Alexagate, is the latest effort from MSCHF, a Brooklyn-based startup that makes limited-run products with a rhetorical flourish. In this case, MSCHF’s point of view is that Amazon is snooping on users through its Echo speakers, and that users should have an easier way to turn off the mics. Kevin Wiesner, MSCHF’s creative director, calls Alexagate an “aftermarket privacy adjustment” with an adversarial bent.

“We have a device, it’s in our homes, it’s essentially a wiretap sitting on a coffee table,” he says. “Let’s retrofit it, essentially, so it behaves the way we would want it to, and not necessarily the way Amazon wants it to.”

Alexagate is more of a stunt than a legitimate gadget. MSCHF is only selling a small batch of them—Wiesner won’t say how many—and my experience using the device has been iffy. But even if you’re not among the group of people who buy one, you should hope that its ideas gain traction.

“BYE BYE BEZOS”

Contrary to popular belief, Amazon’s Echo and other smart speakers do not constantly upload audio. They do, however, constantly listen for a wake phrase—”Alexa,” in the Echo’s case—using an on-device processor. You can disable the mics on these devices, but only by walking up to them and hitting a mute button. Most people won’t bother to do that, so the mics are effectively on all the time, always listening for your commands.

Alexagate isn’t an entirely original idea. In early 2019, Tellart designer Bjørn Karmann and Topp designer Tore Knudsen showed off a set of Amazon Echo and Google Home speaker covers that resembled parasitic fungi. The project, called “Project Alias,” used white noise to deafen Alexa and Google Assistant until users activated their speakers with a custom wake word. In February, Ben Zhao and Heather Zheng, computer science professors at the University of Chicago, showed off a “bracelet of silence” that used ultrasound to jam nearby smart speakers.

MSCHF, however, is the first company to ship these ideas as a real consumer product. A clear plastic ring sits between the speaker and the Alexagate unit, with curved spokes on one side and flat ones on the other to fit different types of Echo devices. (It’s compatible with the first- and third-gen Echo, all Echo Dot models, and the second-gen Echo Plus.) It uses ultrasound, Wiesner says, because it’s more directional than white noise, which would have fooled the triple-clap detection that Alexagate uses to turn Alexa on or off.

But on some level, Alexagate is as much about form as it is about function. The first thing you see when opening the box is “Bye Bye Bezos,” which is printed on the instruction manual. The design, meanwhile, is intentionally conspicuous, Wiesner says, because MSCHF wants it to be a conversation starter. Even if you were to leave Alexa on most of the time anyway, it’d have a harder time blending into the background.

“It’s a bit of a virtue signal where privacy is concerned,” he says. “If I visit someone’s apartment and I see this, part of the implication is they would like me to know that they are actively pursuing a greater protection with their home.”

BUILDING IN BETTER PRIVACY

Although MSCHF’s solution is literally over-the-top, it does call out a couple of underlying issues with smart speakers.

The first is that there’s no easy way to mute them remotely. Instead of having to hit a physical mute button, perhaps Amazon, Google, and others could allow users to shut down their microphones with a voice command or a toggle in their assistants’ mobile apps. They could even let users synchronize these settings across multiple smart speakers, so that setting the home to a more private state would be as frictionless as playing music or checking the weather.

On a more fundamental level, Alexa and other devices just need to get better at understanding when they’re not being spoken to. Too often, these devices misinterpret similar-sounding phrases as wake words, and they have no understanding of intonation, which means even in-passing mentions of “Okay Google” or “Alexa” get picked up as triggers. The response can be unnerving for users, especially when it results in an unwanted action such as sending out private conversations as text messages.

Steve Teig, the CEO of voice and video recognition chip maker Perceive, says accurate wake word detection is less of a challenge than it might seem.

“I definitely think these guys with the noise generation are solving a real problem, but it could also be solved in the wake word itself if you simply had enough horsepower in the gadget and a little bit more sophistication in how you build the model,” Teig says.

In lieu of more steps taken by Amazon and others, we’re likely to see more aftermarket products beyond MSCHF’s Alexagate. A firm called Paranoid is working on several smart-speaker blockers, including one that physically pushes the mute button on Echo speakers, another that emits white noise, and a professionally installed circuit modification that physically cuts access to the speaker’s microphone. In all cases, saying the phrase “Paranoid” disables the blocking. A Paranoid spokeswoman says the products are six to eight weeks away from shipping.

Wiesner says he wouldn’t mind if other companies carried the torch, even if their designs ended up looking like MSCHF’s.

“We’re not going to make more of them,” he says, “so in that respect, if someone else does, and that distributes privacy protection across a significantly larger number of people’s households, I kind of think that’s a cool outcome.”